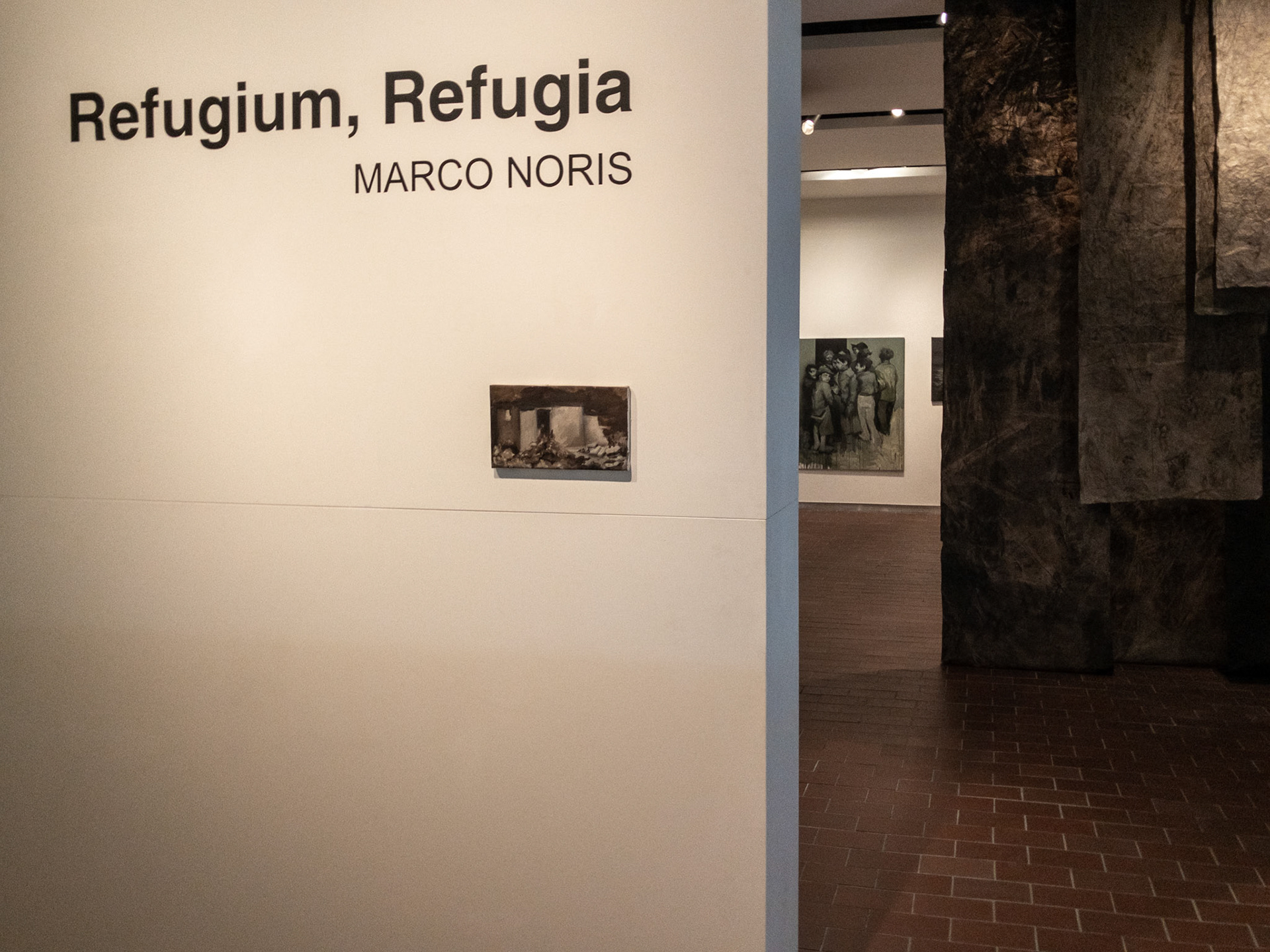

Refugium, refugia

2013/2019

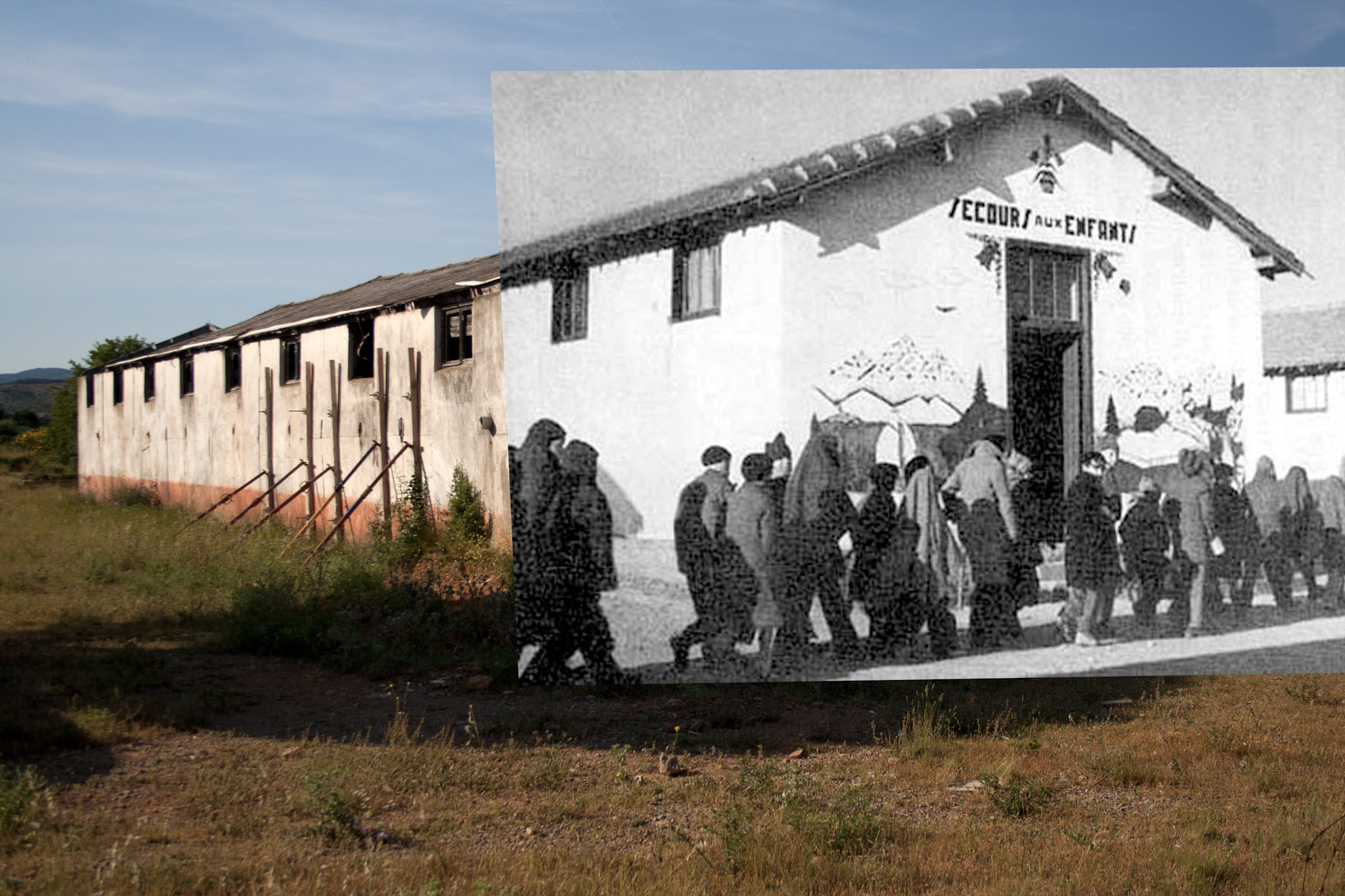

Este proyecto toma el antiguo campo de internamiento de Rivesaltes como punto de partida para abordar la memoria histórica del exilio republicano español. A partir de las ruinas del lugar, el proyecto analiza las huellas arquitectónicas y humanas que configuran una memoria emocional colectiva en la que pasado y presente se articulan.

Exposiciones individuales y colectivas en el Museu Memorial de l’Exili (La Jonquera, 2019), Templo Romano de Vic (2016), Galeria Sicart (colectiva, Vilafranca del Penedès, 2016) Galeria Cànem (colectiva e individual, Castellón, 2016).

Series de obras

Textos y paratextos (1)

Hace algunos años, durante una visita al Museo del Exilio de La Junquera, Noris se encontró por primera vez con la historia del campo Joffre de Rivesaltes, un antiguo campo de internamiento situado en el sur de Francia, abierto en la década de 1930 para acoger a los exiliados republicanos españoles. Lejos de ser un episodio puntual, el campo permaneció operativo durante casi setenta años: fue utilizado como campo de concentración durante la ocupación nazi y, posteriormente, como lugar de internamiento para los harkis argelinos tras la descolonización. La historia de Rivesaltes atraviesa de forma transversal el siglo XX europeo y condensa algunos de sus episodios más traumáticos. Por ello, se revela como un territorio desde el que abordar una investigación sobre la violencia, el desplazamiento forzado y las fracturas de la historia contemporánea. Más que un lugar físico, Rivesaltes es hoy —cuando las ruinas han cedido su protagonismo a la memoria— un espacio emocional colectivo.

Rivesaltes, el pasado es presente, 2013

La memoria de Rivesaltes resuena en la realidad actual de los campos que, en distintas regiones del mundo y en las fronteras de Europa, continúan alojando a millones de vidas desplazadas. Sus ruinas operan como un umbral entre pasado y presente, conectando la historia del siglo XX con las políticas migratorias contemporáneas.

Sin embargo, este proyecto no aspira a constituirse como una investigación histórica. La historia funciona aquí como punto de partida para un desplazamiento por la memoria emocional colectiva, en busca de una experiencia que, partiendo de lo individual, aspire a una dimensión universal, más allá de épocas, fronteras y nacionalidades.

Refugium, refugia nace de ese espacio devastado, testigo y víctima de múltiples tragedias humanas. Para Noris, Rivesaltes no es un tema histórico, sino un punto de partida para interrogar los vínculos entre memoria, desarraigo y presente. Las ruinas del campo se enlazan con los actuales centros de internamiento y los campos de refugiados que, en las fronteras de Europa y del mundo, perpetúan el mismo drama de la exclusión. El trabajo propone así una reflexión sobre la continuidad entre los campos del pasado y los dispositivos contemporáneos del control migratorio, donde la historia reaparece bajo nuevas formas políticas y materiales.

El título de la exposición remite al término latino refugium, que designaba tanto un lugar de huida como un retorno, una vía de escape o un espacio de resguardo. En su plural, refugia, la palabra evocaba también los escondites domésticos donde proteger los bienes ante el peligro. Noris se apropia de esta ambivalencia —reparo y huida, recogimiento y desplazamiento— para abordar el refugio como estado de tránsito permanente, como síntoma de una vulnerabilidad estructural.

Refugium, Refugia. 2019, MuMe - Museu Memorial de l’Exili, La Jonquera, España

Las obras reunidas en Refugium, refugia exploran los paisajes físicos y emocionales del exilio: fosas, túmulos, cajas o agujeros que funcionan simultáneamente como refugio y condena. Estos lugares condensan la tensión entre la necesidad de amparo y su negación, y señalan la pérdida de identidad y dignidad que define la condición del refugiado.

En este contexto, la figura del desterrado se convierte en un paradigma universal: aquel que, incapaz de regresar a su hogar, queda también imposibilitado de habitar otro. Para Noris, el desarraigo es un trauma irreversible que toca los fundamentos mismos de lo humano, un eco persistente que conecta los pasados de la historia con las heridas del presente.

(In)refugios, 2016

(In)refugios. 2016, Temple Romà, Vic, España

(In)refugios. 2016, Galeria Canem, Castellón de la Plana, España

Este proyecto ha sido posible gracias al soporte de La Escocesa y Hangar, centros de creación en Barcelona. También agradezco a Jordi Font, Miquel Serrano, Alfons Quera y todos los compañeros del MuME, Paula Bruna, Carlos Puyol, Miquel Bardagil, Mireia Martínez i Raül Segarra, Tere Badia, Kike Bela, Antonio Bela Armada, Pep Dardanyà, Piramidón, Yann Molina, Elodie Montes, Judith López, Pilar Mestre, Mar Arza.